Effective Nationalization of Corporate Credit

The context of this article is the United States economy. The ideas presented should apply to other countries as well, but I will limit the scope to the US for the sake of clarity.

Modern Economics

The work of John Maynard Keynes strongly influences economic thinking within governmental circles. Keynesian theory advocates active, centralized management of the economy, in particular during times of looming recession. As an economy dips towards recession, for example, central planners prescribe increased government spending—the thinking: government spending provides jobs, which increases spending by people newly flush with money, which in turn employs more people, which increases spending by people flush with money, . . . rinse; repeat.

Similarly, when the economy is operating outside of the extremes, central planners nudge the trajectory of the economy by manipulating interest rates: increased to prevent excessive growth and burnout; decreased to stimulate investment and growth.

The Actors

The credit markets comprise many actors, each with different driving motivations. Two major actors are

The Federal Reserve — the central bank of the United States

The United State Treasury — the entity that receives collected taxes and manages, as directed by Congress, the national debt

The Federal Reserve manipulates interest rates with two principal objectives:

Maximum employment

Stable prices — via an approximate 2% annual inflation rate target

So far, we have introduced the concept of interest rates without definition. A variety of interest rate types exist, but for our purposes, in the following sections, we'll discuss three: Treasury interest rates, the federal funds rate, and corporate interest rates.

Treasury Interest Rates

When the Treasury wants to borrow money, they may issue a Treasury bond. A Treasury bond is simply a promise by the Treasury to pay a set amount of money to the bondholder—say, for example, $10,000—at some set time in the future. Since we value money in hand today more than promised money in the future, these bonds sell for less than their $10,000 face value. One can interpret this price difference as an effective interest rate. Confusingly, the price of a bond fluctuates. If the price goes up, the effective interest rate goes down, and vice versa.

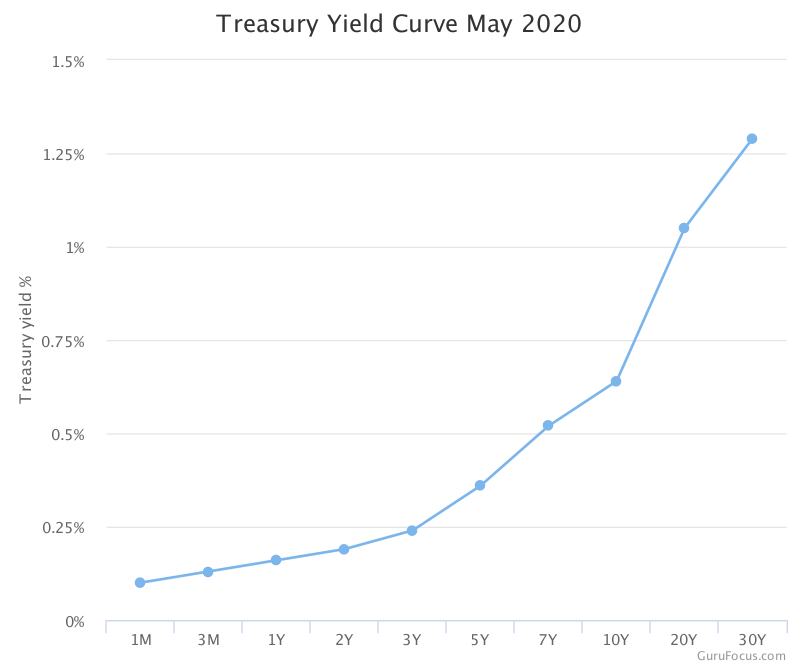

Now, not all Treasury bonds pay the same interest rate. The payout period of a Treasury bond can vary between one month and 30 years. Interest rates on later maturing treasuries are generally higher than shorter terms. How Treasury yields change according to maturity term is called the yield curve.

Federal Funds Rate

The federal funds rate is an interest rate set by the Federal Reserve that banks use to lend to each other overnight. In some respects, this is the most significant interest rate since it sets a baseline, or a rate floor, for other short term lending rates. As of this writing, the federal funds rate is 0.1%.

Short term treasuries often earn interest at rates at or approaching the federal funds rate. Market forces generally ensure this relationship.

Corporate Interest Rates

As governments issue bonds, so too can corporations. While the risk associated with treasury bonds is considered negligible (no risk of default), corporations can go bankrupt and fail to honor the full amount of their loans. The market puts a premium on risk. Corporate bonds come with increased risk; therefore, investors will require a higher interest rate than offered by the near zero-risk treasury bonds.

Corporate bonds are each graded for risk of default. Therefore, interest rates can vary widely from company to company, bond to bond. Corporate bonds allow companies to secure loans without a bank by enabling professional or everyday investors to fund companies directly, and in the process, earn interest.

How the Fed Sets Interest Rates

In the most simplistic terms, the Federal Reserve sets the federal funds rate. This centrally managed rate, as we hinted previously, serves as an important, if indirect, influence on other lending rates, which are otherwise governed by normal market forces. If the Federal Reserve wants to reduce long-term treasury interest rates, it might buy long-term treasuries on the open market. The capital needed to purchase these treasures comes in the form of credit to the banks which supplied the treasuries. This increase in available credit has the effect of increasing the total amount of money in circulation.

During the financial crisis of 2007, the Federal Reserve also bought mortgage-backed securities. This action helped bring mortgage rates down to a level closer to the artificially lowered rates of treasuries.

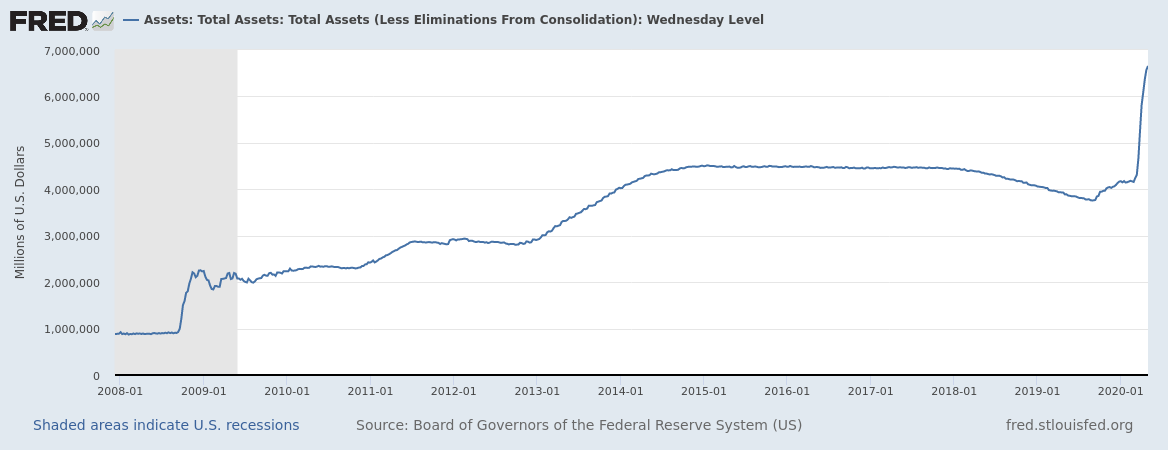

In theory, the Federal Reserve operates this way because it can undo everything. The Federal Reserve creates money and buys treasuries, but they can also sell treasuries and destroy money. Though, in practice, the Federal Reserve has not unwound purchases for over a decade. Below is a graph of the total amount of assets that the federal reserve owns.

As illustrated, during the 2007/8 financial crisis, total assets rose quickly from $1T to $2T, but then grew more slowly from $2T to $4T. Following this, we see a bump after a small unwinding took place in lead up to the financial markets becoming stressed. Unsurprisingly, a steep increase from $4T to $6.5T occurred in response to the coronavirus, and I doubt it will stop there.

A New Asset For the Fed

Stress in the financial system was apparent in September of 2019. The response to COVID-19 has only made these stresses more visible and severe. Social distancing has served to suppress economic activity for many companies. One concern is that corporations might not be able to borrow and may be unable to service existing loans. To avoid resulting bankruptcies, the Fed has set up two facilities that will buy corporate loans.

Lending money to corporations involves some amount of risk. However, the Fed's risk exposure is very different than to what a retail investor experiences. If a company defaults on a bond purchased by the Federal Reserve, the Treasure insures the exposure with money set aside for this purpose. This means that the Fed can buy corporate bonds at effectively no risk.

Under normal operations, there is a beautiful dance that happens in credit markets. Investors evaluate the risk vs. reward for particular bonds. If an investor evaluates that the reward is worth the risk, the investor might decide to purchase the bond. Each purchase by these investors will then slightly reduce the value of that reward—from a broader market perspective.

Several motivations are at play when the Fed takes action. Purchases by the Fed reduce the reward that corporate bonds offer without a corresponding evaluation of the associated risk. Investors who understand this will most likely stay out of the market. As general investors walk away, this puts pressure on the markets to have the Federal Reserve step in and inject more cash. This scenario effectively leads to a nationalization of the credit markets.

Counterthoughts

Some investment advice I try to keep in mind is, "invest in what you know." This suggestion makes a lot of sense. How can you do better than other market actors unless you have a better understanding of the fundamentals? So perhaps a take away from this article is, if you were an expert in corporate bonds before, maybe some outside analysis should be brought in to account for the actions of the Fed. The market is a different animal now.

The fact is, all investments are relative, and markets are complex. The purchase of bonds by the Federal Reserve may help keep businesses afloat. Maybe? In that case, bonds will actually be worth more with Fed action than without. The Fed's actions might raise the price of corporate bonds, but corporate bonds are still better than other options for certain investors.

It is worth noting that the Fed's recent round of corporate bond buying is not without precedent. The Bank of Japan has been buying corporate bonds for a while now. Their economy failed to stabilize and now the Bank of Japan is buying equities(stocks) outright.

Darren Tapp

Darren Tapp